Dennis Severs’ house, Spitalfields

I’ve loved Dennis Severs’ house in Spitalfields ever since I first lived in the area 15 years ago. I would walk past the townhouse with the red shutters and the silhouette of an 18th century lady in the upper window nearly every day and admire it. I've visited the house several times before, and it's a particularly special place at Christmas time, when the house is wonderfully decorated both inside and out.

Dennis Severs was an American who moved to Spitalfields in east London in 1979—Spitalfields was still mainly known at that time for its fruit and vegetable market. Its streets of fine early Georgian houses were originally built for Huguenot silk weavers and merchants, but many had fallen into disrepair and were by now under constant threat of demolition and redevelopment as the nearby City began to encroach on land that had once been the site of a medieval priory outside London’s walls. The ruins of St Mary Spital (which gave Spitalfields its name) can still be viewed beneath the pavement outside the huge office block belonging to Allen & Overy on Bishops Square.

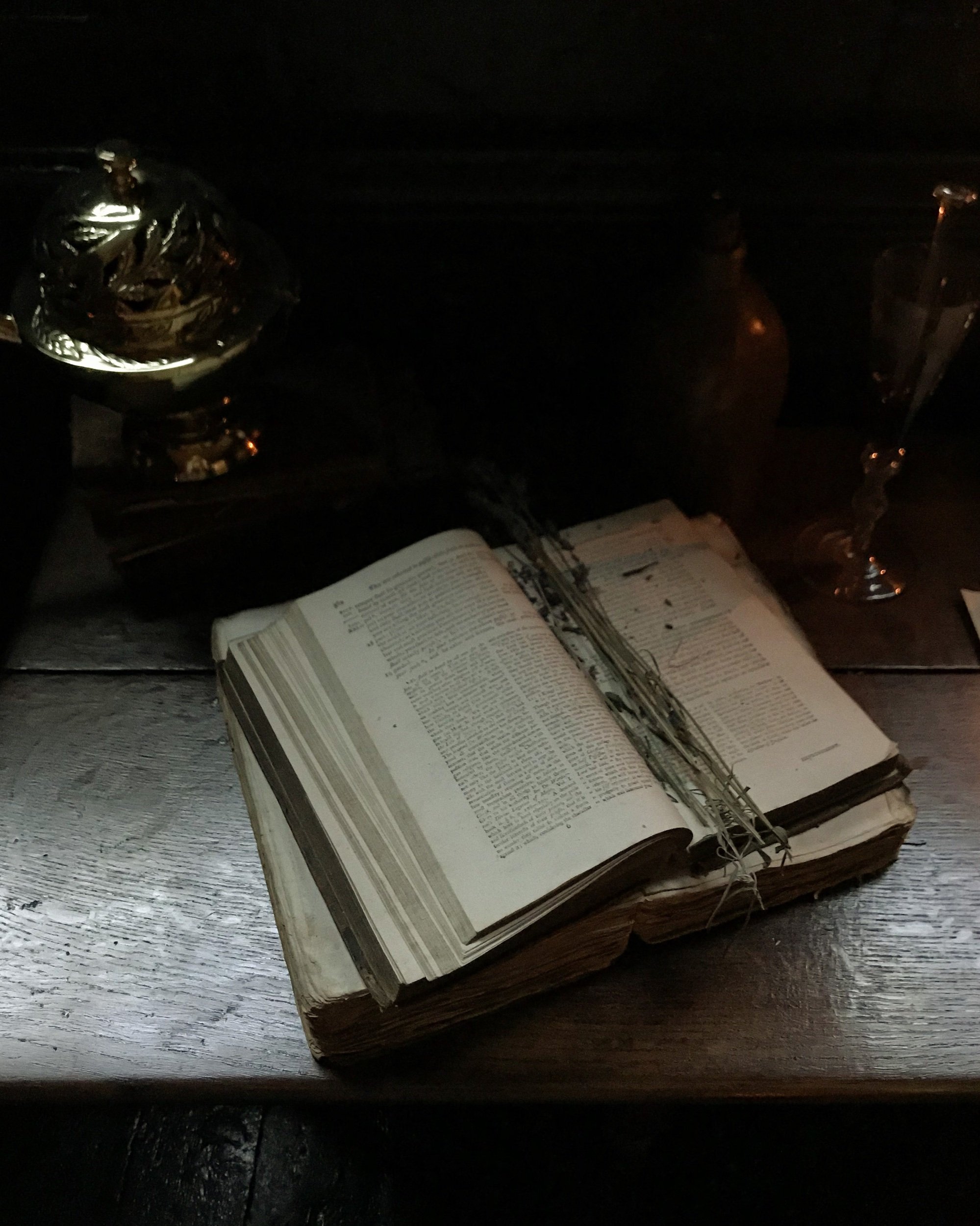

Dennis Severs bought a dilapidated house at 18 Folgate St and restored it, although that’s not quite an accurate description of what he did—he was interested in the house’s “atmosphere”, and his aim was to try and re-create its former life via a series of 10 rooms which he brought to life as multi-sensory evocations of the past. He imagined a history for the house: a Huguenot family called Jervis whose members lived in it through the centuries—from the time of Spitalfields’ boom in the early to mid-18th century through to the poverty-stricken 19th century, when French silk imports had decimated the English silk trade and the weavers of Spitalfields lived a desperate, hand-to-mouth existence. This change in fortune is reflected as you progress through the house, from the sumptuous ground floor rooms up to the attic.

The family he conjured up seem as if they might return at any minute to finish eating the food left on plates or to snuff out the candles burning in every room. He created subtle sound effects for each room, and allowed no artificial electric light. It’s an interesting and very effective conceit, because from the moment you enter the hallway you feel as if you’ve been transported to a different time, one with its own sounds, smells and sights.

The house today belongs to a trust who care for it and run tours, and I’ve always lamented the fact that photography isn’t allowed inside, although you can understand why—that unique atmosphere would be destroyed if there were hordes of people taking photos or posing for selfies in the house. And yet it’s such a magical place that you long to take photos of it. So I was thrilled a few years ago to be invited to take some photos of their Christmas installation, which runs throughout December each year. It’s one of my favourite things to do in London at Christmas time and I’d highly recommend it.